5 Buyouts

“[T]he only way to guarantee something is not going to flood is to do a buyout.”

—District Planner

Planning’s necessary contribution to incorporating and strengthening hazard mitigation can be best illustrated by diving deeper into a specific mitigation strategy, such as land acquisitions. Land acquisitions generally refer to the “purchase of private property by government for public use”,51 while buyouts are “a specific subset of acquisition in which private lands are purchased, existing structures demolished, and the land maintained in an undeveloped state for public use in perpetuity”. Another term related to this strategy is “relocation,” which implies the structure and/or the household removed is subsequently re- established at a new site. Out of all the mitigation strategies available for flood hazards, land acquisitions are arguably the most significant to planning as it promotes the active demolition of the built environment. Rather than viewing this as a loss, planners have the tools and skills to promote this strategy as the first step in the process for developing safer communities in an climatically uncertain future.

Overview

One of the “public measures to promote improved land use,” as Gilbert F. White wrote, was land acquisitions, which had been “suggested by many as a means of promoting desirable shifts in land uses.”52 As early as the 1930s, Gilbert F. White discussed three early US cases of “urban relocation”, a type of land use change, where “complete, outright changes in the urban units” were made in response to flooding.53 These cases spanned from the late 1920s to the early 1940s, before there was explicit federal support (monetary or otherwise) for such interventions. Funding was raised locally, secured from other supporting organizations such as the Red Cross or acquired through loans, e.g. from the Disaster Loan Corporation. Other challenges he noted were “social interia, the attractions of floodplain locations and the task of organizing group action.”54 Despite these roadblocks, White praises this particular adjustment because of the possibilities it can unlock for communities. “Relocation may also stimulate new life, and induce urgently-needed community reorganization...Properly designed and executed on a favorable site, relocation stimulates civic improvements and revitalization.”55

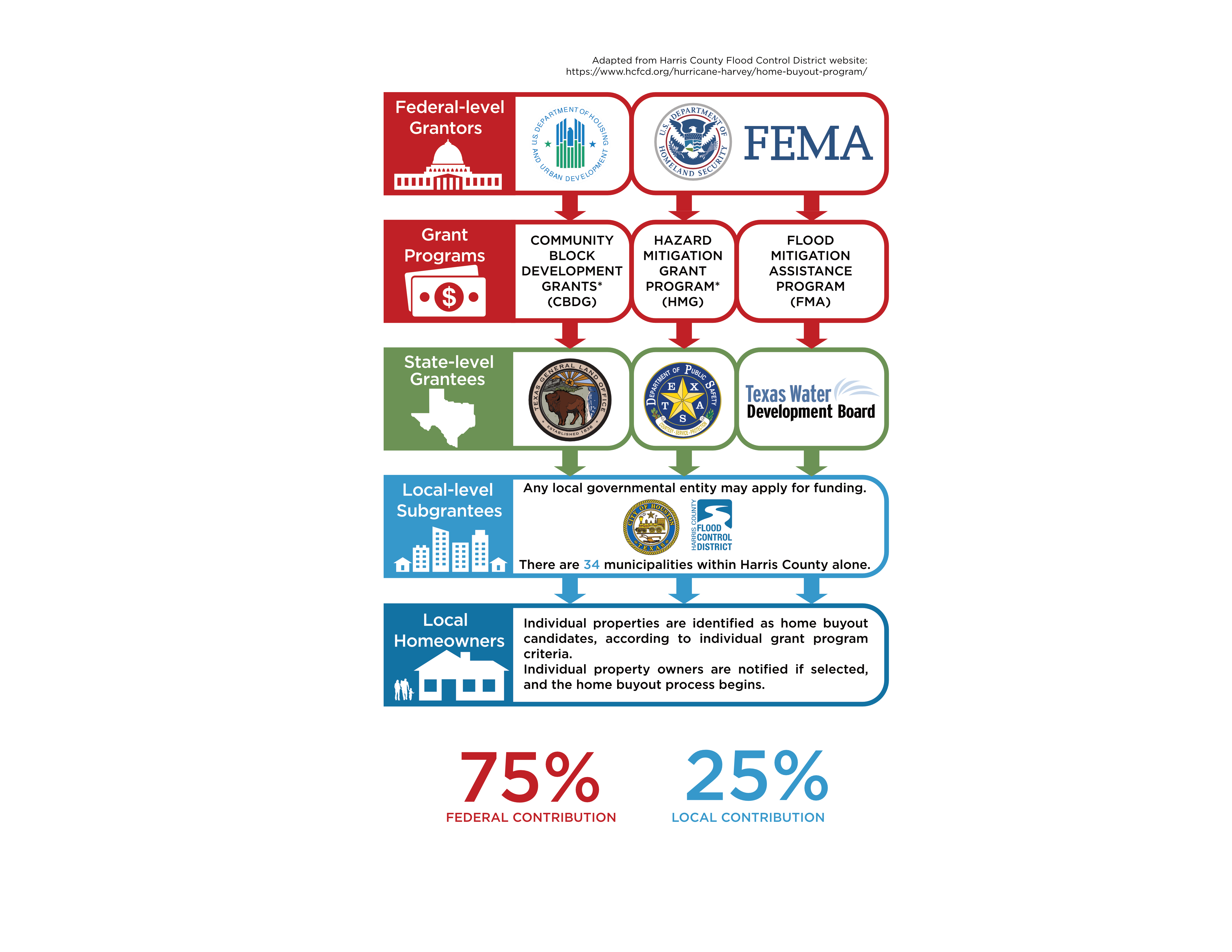

Fast-forwarding to more recent times, though relocating homes has always been an option for communities (with or without federal support), the strategy of acquisition became more popular and federally supported after the Great Mississippi and Missouri Floods of 1993.56,57,58 Currently, there is federal support available for both pre- and post-disaster buyouts as part of a larger mitigation strategy for a community. Often, buyouts are pursued post-disaster during recovery process while the federal grant programs structured for and encourage more of a long-term mitigative approach, which adds to the difficulty for communities to take advantage of the strategy.59 Nonetheless the process of federally- funded buyouts can be described as the following steps:

- Assuming a presidential disaster has declared, a mitigation plan is in place, the community participates in the NFIP and an administrative agency identified, a criteria is developed to determine properties that will be eligible for the local buyout program.

- Property owners will be contacted and willing sellers will be added to the application that the state will submit on the local government’s behalf.

- If the application is approved, the federal funding will cover 75% of the total costs,leaving the other 25% as the responsibility of the applicant. If the applicant does not have the 25%, a Community Development Block Grant can be applied for and used to cover this portion of the cost.

- The funding is then dispersed back to the local government, which can then compensate property owners for the pre-disaster market-rate value of their property and presumably fund the move to safer housing. (see Figure 8)

Buyouts of this nature have been done for the last few decades and, similar to what White found with the earlier version of the process, there are still many drawbacks that make the process undesirable to pursue outside of a last resort. In particular, there are two common major disincentives that contribute to its controversial reputation.

“I don’t even know if our government could even afford this whole buyout.”

—Flood Victim

Figure 8. The Buyout Process

Insert Arbor Oaks Callout

Buyouts Are About Money

Buyouts are expensive. One city planner interviewed as part of this research openly disagreed with buyouts as a more prominent flood mitigation strategy for Houston, stating that it was not “optimal”. The financing was too “complex.” Buyouts, and related acquisitions, are often stifled by questions of adequate funding, sources of funding and defendable uses of funding.

The idea of purchasing every home within a floodplain in Houston is unfathomable but, even to a lesser extent, there are still issues of ‘How many homes for how much?’ The cheaper the properties, the more that can be bought out within an area, making it easier to achieve the outcome of a wholly floodable open space. As a District planner pointed out, “[The District has] received much less funding to do buyouts than to do other structural projects,” leaving the question of how much impact can be made within the budget available. This was significant issue for the city councilperson interviewed whose central concern was funding. “[H]ow can you say, ‘Okay, in this neighborhood...We need to do a buyout program...’ or what have you when you don’t know what money you will have to actually provide those resources for people?” In short, you need money to compensate property owners.

The issue of adequate funding is in concert with the issue of the source(s) of funding. As outlined earlier, the federal government does make available grants for buyouts in flood-impacted areas. Because of this, there is little incentive to break that dependence. “We will not have money for buyouts,” said a city planner, “we rely on federal grant money for such efforts.” This dependence unfortunately comes with its own consequences for the residents, which was an issue of focus for the environmental lawyer. Since buyouts are often pursed post-disaster with mitigation funds, the release of these funds from the federal level down to the citizen is a slow process. “Buyouts are best served right after the storm but that doesn’t happen because the money isn’t there yet,” lamented the lawyer, which is true given that participants need to be identified for the application to be submitted.

There is also an argument for the cost effectiveness of buyouts as well. Related to the issue of how much of an impact the strategy can have on a limited budget, there are arguments for alternative uses for the same amount of money to reduce flood risk using other mitigation approaches. A District planner did counter that “[t]here may be more of a benefit on doing some of those large scale channel improvements,” especially in areas that are not too deep into the floodplain. It’s a larger policy question for local governments also about whether using public funds to remove homes is appropriate, especially given the US history of urban renewal.60

“In this arena, it’s not seen as an actuarial calculation.”

—County Planner

Buyouts Are NOT About Money

Buyouts are more than a money problem. The same dissenting city planner dismissed buyouts also because they lead to “lots of unintended consequences.” Buyouts are disruptive to the built environment and can negatively impacted participants and non-participants alike. As a process it neglects the power of place and social networks and is indifferent to the creation of new homes, new lifestyles and new space in the aftermath.

Buyouts inevitably remove people from their homes and that is no easy task. Because buyouts are voluntary, residents can still choose not to move and remain living in vulnerable areas. The memories of a place cannot be bought or replaced and that needs to be better respected within the buyout process.

The pursuit of buyouts is that it dismantles communities, parcel by parcel. Because the decision to participate is ultimately made at an individual household level, there is no guarantee that neighbors or whole neighborhoods can move together to a new location. This attritional loss of households does not account for the social networks built within a community nor the networks extended outward (jobs, schools, etc.) Such lack of consideration in the existing process dissuades community buy-in and also ultimately leads to households continuing to live in highly vulnerable areas.

Although some of the more historical examples describe a relocation process, less often is there a known destination for those who agree to leave their home. As structured, the buyout process focuses on getting people out of harm’s way, not resettling them elsewhere. Without concern for where people end up, there is no guarantee that they will not return to the same situation. “Some people end up [in the floodplain] because of the low real estate value and figure it is worth the risk,” shared a county planner, and that’s assuming they are even aware of the risk to begin with. The private consultant had worked with a community in that exact situation that bought their land because it was cheap and in the floodplain, but subsequently had no place to move.

One of the flood victim’s loved their neighborhood and was quite aware that if their family chose to move that they’d have to move out of the neighborhood because “there is nothing else in this area [that’s] going to be in [our] budget anymore.” Buyouts remove housing units with no ties to replacement units, so, for those who would struggle to find similar housing, there is less willingness participate. “There is a reluctance from the low-income community towards buyouts and relocation as there is not equivalent low-income housing available for them to move into,” deduced the environmental lawyer. This also makes it increasingly difficult to stay not only within the same neighborhood, but also city or county, adding to the issue of retaining residents once buyouts are complete.

Lastly, although the process may be complete for the individual, it isn’t unusual for it to be incomplete across the eligible neighborhood. Because buyouts are voluntary in nature, as referenced before, property owners can choose to stay not only in flood-prone areas but sparsely populated subdivisions. “Now you’ve eliminated repetitive loss but now you’ve increased slum and blight, especially in a city like Houston,” pointed out the private consultant.

Even if a site was to be bought out in its entirety, there still may not be a plan for the site afterwards. “[T]hat area, once it’s purchased, can it be used for storage or detention or is it just preservation? Park space?,” asked a county planner, as the potential for buyout sites is often left out of the process and planning for the local area.

Overcoming the social, emotional and design hurdles of buyouts are issues many local communities have yet to face. A balance must be achieved between reducing risk and retaining social capital, which should only encourage planners to engage these issues within the buyout process. Buyouts are in no way perfect but the strategy is still being utilized by communities across the US. The practice of planning focuses heavily on the changes of land uses that result in more development, but further inspection of buyout sites, often purgatorial and sparsely populated suburban neighborhoods, conjure up questions about what it means to intentionally change land uses to decrease development in an area. The transition of land uses that a buyout, or other related land acquisition, causes can and should be better managed through local land use planning. The framework of comprehensive planning can provide the programmatic and community support needed to strengthen the process and outcomes of the strategy. Planning can assist the buyout process by connecting it to community resources as a means of overcoming the well- established issues. To further this point, I looked into four precedent programs at the city level that attempted to connect acquisitions with other ongoing initiatives, specifically to address the issue of available comparable housing.

51 Ann Siders, Paper in proceedings from The 16TH Annual Conference on Litigating Takings Challenges to Land Use and Environmental Regulations: Anatomy of a Buyout — School of Law, 2013), 2.

52 White, “Human Adjustments to Floods,” 190.

53 White, “Human Adjustments to Floods,” 185.

54 White, “Human Adjustments to Floods,” 186.

55 White, “Human Adjustments to Floods,” 188.

56 Elyse Zavar, and Ronald R Hagelman III, “Land Use Change on U.S. Floodplain Buyout Sites, 1990-2000,” Disaster Prevention and Management 25, no. 3 (2016), 362.

57 Alex Greer and Sherri Brokopp Binder, “A Historical Assessment of Home Buyout Policy: Are We Learning or Just Failing?,” Housing Policy Debate 27, no. 3 (2017), 373.

58 Raymond J. Bubry et al., Cooperating with Nature, 169.

59 Alex Greer and Sherri Brokopp Binder, “A Historical Assessment of Home Buyout Policy: Are We Learning or Just Failing?,” Housing Policy Debate 27, no. 3 (2017), 376.

60 Renia Ehrenfeucht and Marla Nelson, “Moving to Safety? Opportunities to Reduce Vulnerability through Relocation and Resettlement Policy,” in How Cities Will save the World : Urban Innovation in the Face of Population Flows, Climate Change and Economic Inequality, ed. Ray Brescia and John Travis Marshall (London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016): 65-79.