4 Case Study

Houston

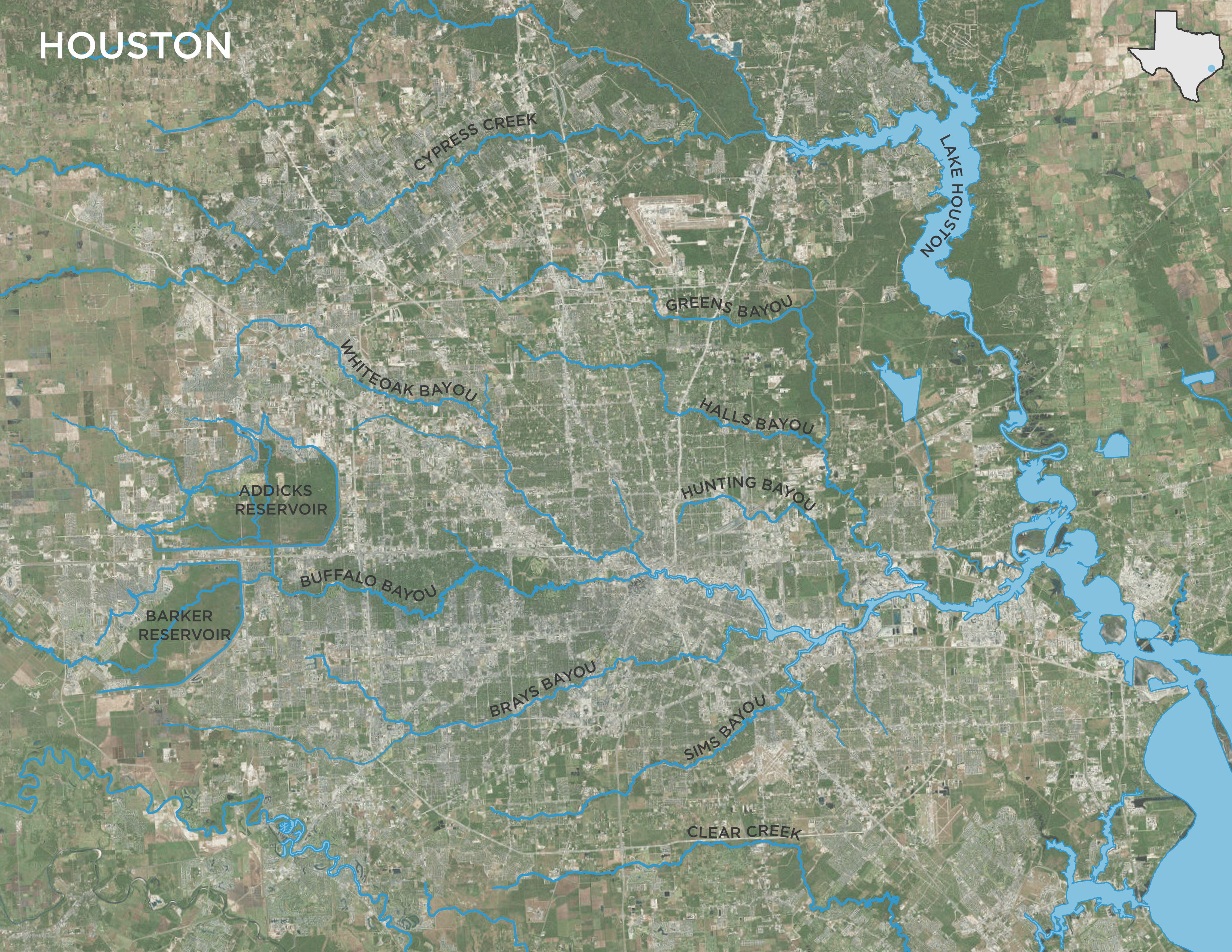

Houston, TX is well-known for many things: it’s the largest city in Texas and fourth largest in the country,29 it’s home to the NASA’s Johnson Space Center, it’s a major petrochemical hub for the country, and it’s the largest city in the US without a zoning ordinance governing land use.30 Houston, the seat of Harris County, is lesser known for its natural environment, earning it the nickname “Bayou City.” Houston sits within the Gulf Prairies and Marshes ecoregion of Texas, which is characterized by its gradual sloping topography towards the Gulf of Mexico and many rivers, creeks and bayous that carved through what was once mostly wetlands. Although these waterways were sources of national and international commerce, as the city quickly grew, they turned into sources of catastrophic destruction. Houston’s continued growth, both rapid and sprawling, is at an increasing tension with its dynamic and extensive floodplains. In addition, Houston is one of many Gulf Coast communities that is subject to the Atlantic hurricane and tropical storm season.

Figure 3. Houston Overview

The Houston area has a long history of flooding, but there a few major events prior to Hurricane Harvey worth noting. First, the Great Flood of 1935 nearly wiped Houston off of the map after a “torrential rainfall” over Harris County.31 The flooding occurred predominantly down Buffalo Bayou, the bayou that flows through downtown Houston, and stimulated the subsequent building of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs further upstream and west of the city. These were the first projects of the newly established Harris County Flood Control District (“the District”), which is a special use district (separate from Harris County) to serve as the local partner for the Army Corp of Engineers (ACoE).32

By the late 1960s, the US federal government had transitioned from a long history of federally-funded structural approaches for flood mitigation to a non-structural approach through the creation of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Joining the program, communities gained their first Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) that delineated special flood hazard areas (SFHAs) that would determine insurance rates and premiums.33 Houston received its first flood maps as early as the mid- to late 1970s, and, by 1985, the District expanded its own practice to include non-structural mitigation strategies through the initiation of its Home Buyout Program.34

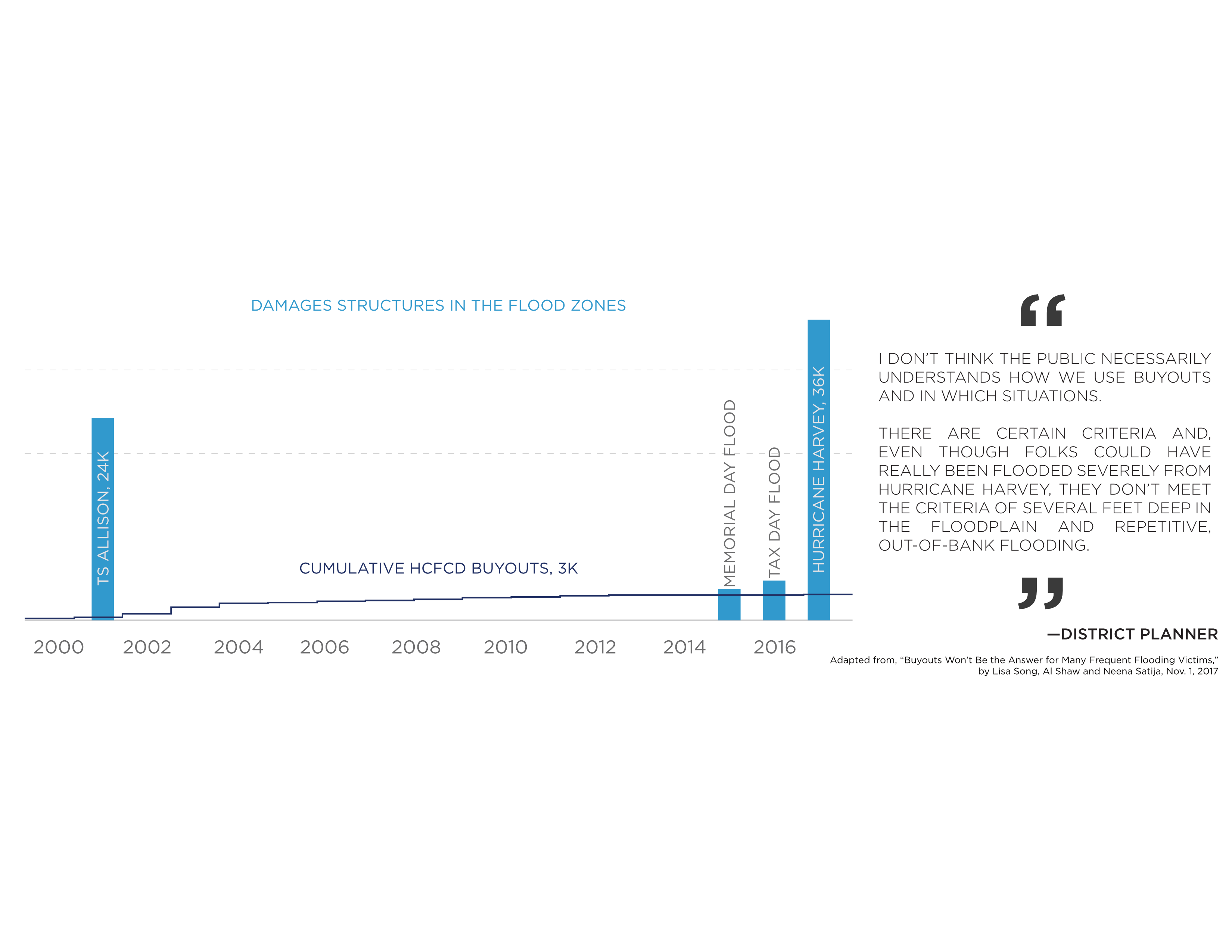

Another notable event was the arrival of Tropical Storm Allison in 2001. Up until this point in the city’s history, the rainfall from Allison had caused the worst flooding observed in Houston. In the aftermath of Allison, FEMA and the District diligently created information available to the public about why Allison was so devastating and how the flooding happened.35 This was followed by two more recent and notable flood events: the Memorial Day Flood of 2015 and the Tax Day Flood of 2016. Both of these events were more intense than a 100-year, or 1% chance, rainfall,36 leaving some residents still recovering from the last storm by the time Hurricane Harvey arrived.

Hurricane Harvey

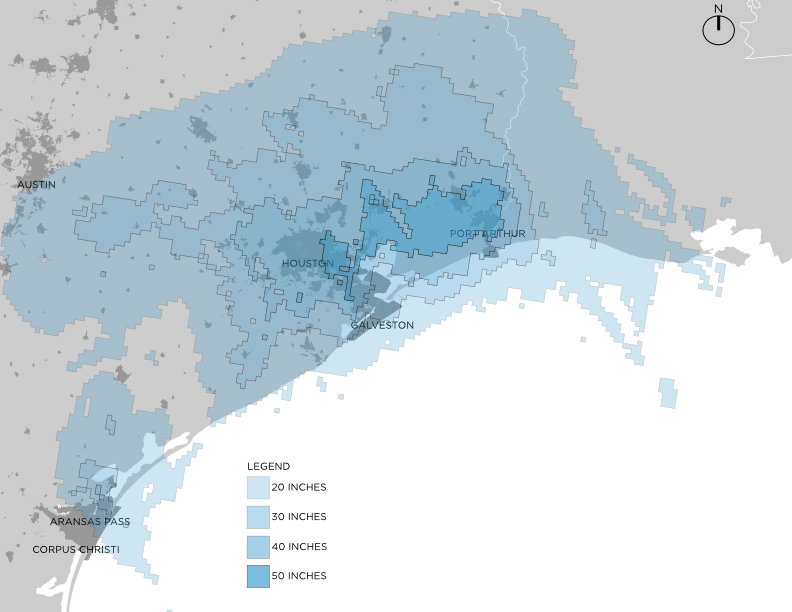

Hurricane Harvey made landfall near Rockport, TX on August 25, 2017, at which time it was a Category 4.37 The storm then travelled north up the coast, where it stalled over the Houston metropolitan region from August 26th to August 30th before continuing northeastward and dissipating inland. During that time, over 19 trillion gallons of rainwater fell over Texas,38 causing catastrophic flooding of biblical proportions. No stormwater infrastructure in the country would have been able to withstand such intense rainfall, as much of the City of Houston received 40-50 inches of accumulated rainfall over those four days (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Harvey Rain Accumulation

Over 300,000 housing units were affected in Houston, which was more than what was observed post- Katrina or post-Sandy.39 As a resident involved in a local nonprofit pointed out, “Flooding usually occurs in one part of the county. Harvey flooded most of the county.” Harvey was impactful not only in its intensity but in its scope. Although there were those who had flooded before and flooded once again when Harvey arrived, there were also those who had never flooded before nor knew they were vulnerable to flooding, and this is where the tension for recovery now lies.

As images showing the apocalyptic flooding in Houston and surrounding areas began to circulate through televised and online media, so too did opinions on what led to Houston’s demise. Large news outlets, such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic all covered the storm and its speculated exacerbation through Houston’s overdevelopment in recent years. Given the absence of the traditional zoning model in Houston, its minimal land-use regulations and market-driven approach to development have become the popular scapegoats for why flooding was so bad.

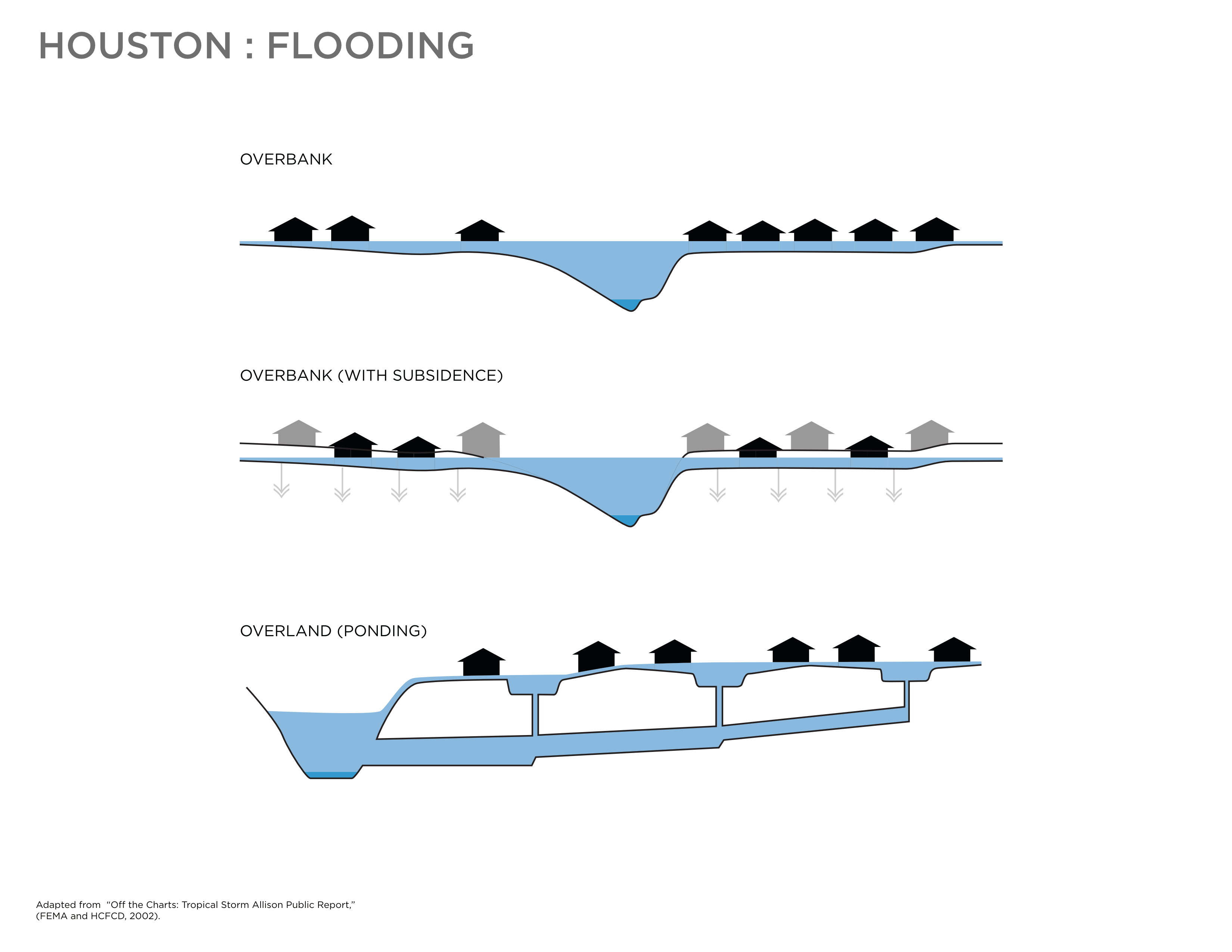

“With these storms, you get trillions of gallons of water dumped on a place, floodplain or not, it’s not gonna be able to withstand that, right?” posited the city councilperson during our conversation, as a storm like Harvey would have left any city unprepared. Because Harvey was so unprecedented, there were more nuances in the causes of flooding and, thus, the kinds of flood victims. There are several ways in which flooding is experienced in the greater Houston area, but some causes are quite common (see figure 5). What Harvey added was the overwhelming of existing stormwater infrastructure that led to an overwhelming amount of residents being flooded outside the designated floodplains.

Figure 5. Flooding Typologies

As mentioned before, it was a horrific flooding event that led to the creation of the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs in the 1930s and ‘40s on what was just open farmland far west from the city. Although storms have become more frequent and intense for the region, the capacity and maintenance of the reservoirs has not changed in response. When Harvey made its way over to the Houston area on August 26th, 2017, the reservoirs were almost immediately overwhelmed, causing flooding for the upstream surrounding communities. The decision was made by the ACoE to begin controlled releases from Barker Reservoir to reduce further risk of compromising the structure, with full knowledge of the consequential flooding of neighborhoods downstream from the reservoir along Buffalo Bayou.40 In addition to the environmental factors that have historical contributed to Houston’s flooding, government action has now added to the complexity of how the city will recover.

The city of Houston is now having to grapple with those who were flooded and outside of a designated SFHAs,41 both unintentionally and intentionally. This new experience has added to the reluctance to rebuild by some who now fear their newfound vulnerability, similar to the experience of being “burglarized” as described by the private consultant. Although there are critiques of the accuracy of FIRMs and designated SHFAs,42 Harvey has surely brought to light for the city that more people are potentially at risk than any current maps have captured in a time of increasingly frequent and intense rainstorms for the region. Thus, in addition to those who have already weathered many storms in Houston, first-time flood victims are also adding to the conversation of what more can be done about Houston’s precarious existing development.

Within the larger media discussion about Houston’s planning, or lack thereof, as the major contributor to the worst flooding in the city’s history, a more targeted debate grew around the increased stock of damaged and vulnerable structures in the city. A prominent stance in the debate is the need for more buyouts in the Houston area. Although the city and county have made great strides post-Harvey to adopt stricter development guidelines and building codes,43,44 those regulations only affect new development and major redevelopments, leaving a wider arena of discussion for the possibilities for addressing existing development.

In particular, a growing critique of buyouts is not surrounding the social and economic implications, but that enough have not been done.45 What is confounding about the public discourse for more buyouts in Houston is its juxtaposition to the city’s reputation for staunch private property rights protection. However, because of its lack of the traditional land use regulation model of zoning, the city can be seen as a radical experiment for alternative land use management practices. Despite its history of deregulated land use, which is viewed as conservative in nature, Houston has openly embraced more progressive and aggressive flood mitigation strategies, such as acquisitions. And just how have land acquisitions become amenable in such a community? By having the District’s long-standing Home Buyout Program.

HCFCD Home Buyout Program

“The name of the district is indicative of the hubris of the time of its creation,” explained a planner at the District because, although the District was originally tasked with “preventing continued public calamity caused by great floods” and constructing “improvements to control flood waters”, even the District realized the folly in trying to “control” floods through solely structural mitigation.46 Thus, the District initiated its Home Buyout Program in 1985. The Home Buyout Program is a voluntary program available to properties within the District’s jurisdiction, which is loosely coterminous with Harris County. Similar to other locally-run buyout programs in the US, the District has a set of criteria that determines the eligibility of properties and prioritizes their efforts within certain areas. In particular, the District focuses on “riverine, out-of-bank flooding”, targeting properties that are “several feet (hopelessly) deep in the floodplain where projects to reduce flooding are not cost effective and/or beneficial.”47 (see Figure 6) The program has target areas throughout its jurisdiction and compensates property owners using a variety of funding sources, although federal funding is the primary source. In addition to compensation for the property, the District’s Home Buyout Program also follows the Uniform Relocation Act (URA) of 1970.48 Typically required for involuntary relocations caused by federally-funded projects, the Districts opts to provide limited support for moving participants to a new, comparable home of lesser risk.

Figure 6. The HCFCD Home Buyout Program Overview

The District’s Home Buyout Program is the most active and long-standing program in the metropolitan Houston area, so, naturally, the District is looked upon to take up the task of increased buyouts post- Harvey. “There’s public perception that the flood control district handles all buyouts in Harris County and that’s not the case,” explained a district planner quite familiar with the program. Given the scope the Home Buyout Program and jurisdiction of the District, it is not possible for the District to solely take on such an endeavor. More specifically, the District does not handle flooding that happens outside the floodplain nor flooding caused by other mechanisms, such as ponding or overwhelmed stormwater infrastructure, given its responsibilities for the waterways and its limited amount of financial resources. There is growing awareness and criticism on the discrepancy between the scale of damage after major flooding events and the number of buyouts achieved through the District’s Home Buyout Program (see figure 7).

Figure 7. The HCFCD Home Buyout Program Historically

Thus, a growing gap has accumulated between the amount of buyouts being pursued by the District and the seemingly increasing percentage of structures at-risk of flooding repeatedly in the City of Houston. Despite the strong stance for buyouts as a more prominent strategy for the city post-Harvey and beyond, it is currently unclear what participation the city itself will have in addressing this gap. News articles since the storm have well laid out this opportunity for buyouts, or land acquisitions more broadly, to be part of a larger, citywide development process for increased resiliency that Houston is poised to undertake. Given this discussion is happening on a large platform, it was imperative to see if and how these ideas were being discussed on the ground.

In Conversation

Having better understood the context of buyouts in Houston, I set out to capture this ongoing conversation from current Houstonians, with the purpose of documenting a variety of stakeholder perspectives on relocation out of the flood-prone areas in the city. Interviewees were further divided into subcategories to better distinguish the multiplicity of perspectives within each (see Figure 1). Through my analysis of the interview data, I sought to triangulate:

- The conditions that Harvey contributed to or created in terms of flood risk in Houston,

- The public discourse captured in the news about the role of buyouts as part of the city’s recovery and

- The way in which buyouts are being perceived and discussed post-Harvey by current Houstonians.

I was interested to learn how Harvey was influencing the conversation around the need for more buyouts in Houston, and, more particularly, if there were parallels between the stance in the news with thoughts from within the city. What I found within in each subcategory were thoughts and perspectives that fit into the larger narrative of how development in the city, both existing and what’s to come, needs to be better informed by the increased risk and vulnerabilities Harvey has brought to light and that Harvey can and should serve as a turning point for more engaged local government intervention.

Only one interviewee had opposition to buyouts as a more prominent mitigation strategy for Houston, as that particular city planner had a stronger alignment to more structural mitigation strategies (increasing detention requirements, widening channels, etc.) Most others felt that buyouts were one piece of the overall recovery and mitigation process for the city moving forward, which isn’t unlike what federal guidance would recommend.49 In digging deeper, there was clear evidence that the interest in pursuing more buyouts than previously attempted prior to Harvey was being discussed even at the ground level. “There were modest buyouts before Harvey. To the extent that we know what the risk is in an area, we should be considering a buyout after Harvey,” stated a resident who worked for a local nonprofit that focused on ecological issues. This stance echoed that which could be seen in similar news articles asserting the opinion that buyouts should automatically be an option for all at-risk development. Another city planner stated that there was a need to be more “aggressive” in pursuing buyouts, that there was a need for more “mandatory requirements” and for more involvement from the city. This city planner suggested something city-driven, as this interviewee saw the at-risk development, particularly those who are already eligible to be bought out, as a health and safety risk for the city. Another resident, who worked for a local nonprofit that focused on neighborhood development in the western part of Houston, supported more buyouts as a means to reduce the amount of development around the reservoirs for fear of dam failure scenarios. It was potential dam compromise that initiated the process of regulated releases and the intentional flooding of bordering neighborhoods, and this interviewee wished to highlight the importance of questioning whether it was reasonable to develop so close to the reservoirs. “If you can’t regulate it, buy it,” stated simply a planner for the District who was familiar with floodplain acquisitions. To this planner, it was clear that regulation was not the answer for Houston, as it has never been, and that to ensure preservation of land in such a place you would have no choice but to buy it.

While the idea of pursuing more buyouts post-Harvey was received well by most of the interviewees, the next hurdle was how those buyouts then could be achieved. The private consultant to local governments tries to “encourage more people to do property acquisitions” but was left with the question of, “How do you encourage local governments to do it?” The consultant shared that such programming is often run at the state or county level rather than the city. For a city to take on such an endeavor, the consultant believe it would have to be a “year-over-year” mitigation process that is planned and targeted. A District planner made it clear that the Home Buyout Program does not need to be the only running program in the area. “There’s 34 jurisdictions within the county that could be doing a buyout program of their own.” Other programs running in tandem could cover the gaps in acquisition eligibility coverage which has been critiqued in the media. Conversely, the same city planner calling for something “city-driven” was hesitant that the city would take on such a project:

“I believe in the past we have always leaned on the county. We’ve never done a buyout program led by the city, and I don’t know what the direction is. I mean having the city kick off a new program like that is a big undertaking. It would not surprise me (but I’m speculating) if we continued to look towards the county. We may be more engaged with the county, in terms of encouraging particular areas to be bought and what not.”

Thus, revealing the problem. Even with the District not meeting the increased interest, there is still hesitancy from a city like Houston to pursue anything beyond that. This led me to larger questions of what the city’s role is in relation to hazard mitigation strategies like buyouts and why wouldn’t a city want to take more agency in mitigation practices that explicitly alter the built environment. What I found is that this roadblock that Houston is facing is not new and that it is tied to the greater discussion of the integration of hazard mitigation into local land use planning. As referenced before it is ultimately the local level that is at the “frontlines of flooding” and other hazards and it is at that level that land use can readily be changed, which has been found to be the ultimate solution to reducing risk, vulnerability and future loss.50 Thorough local land use planning is the key to safer communities in the face of increasing hazards due to climate change and planners have the ability to embed strategies into the comprehensive framework ensuring that it meets its intended mitigation goals.

Insert Callout Box

29 “About Houston: Facts and Figures,” City of Houston, Accessed April 23, 2018, http://www.houstontx.gov/abouthouston/ houstonfacts.html.

30 “Planning & Development: Development Regulations,” City of Houston, Accessed April 23, 2018, http://www.houstontx. gov/planning/DevelopRegs/.

31 Tate Dalrymple et al., “Major Floods of Texas” (USGS, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1939), 226, https:// pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/0796g/report.pdf.

32 “History of the District,” Harris County Flood Control District, Accessed April 24, 2018, https://www.hcfcd.org/about/ history-of-the-district/.

33 “A Chronology of Major Events Affecting The National Flood Insurance Program” (FEMA Contract Number 282-98- 0029, Washington D.C., 2005), 14.

34 “Home Buyout Program,” Harris County Flood Control District, Accessed April 24, 2018, https://www.hcfcd.org/ hurricane-harvey/home-buyout-program/.

35 “Off the Charts: Tropical Storm Allison Public Report,” (FEMA and HCFCD, 2002).

36 “Glossary,” Harris County Flood Control District, Accessed May 5, 2018, https://www.hcfcd.org/glossary/. “An amount of rain having a 1% chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. For Harris County this amount of rainfall is just over 13 inches in 24 hours or just under 11 inches in 12 hours.” Tax Day Floods were greater than a 0.2% chance event (just less than 19 inches in 24 hours).

37 “Major Hurricane Harvey - August 25-29, 2017”, National Weather Service, Accessed May 5, 2018, https://www. weather.gov/crp/hurricane_harvey.

38 “Historic Disaster Response to Hurricane Harvey in Texas,” FEMA, Published September 22, 2017, Accessed May 5th, 2018, https://www.fema.gov/news-release/2017/09/22/historic-disaster-response-hurricane-harvey-texas.

39 “Post-Harvey,” City of Houston, Accessed April 24, 2018, http://www.houstontx.gov/postharvey/index.html.

40 “Flooding Impacts in Connection with the Reservoirs”, HCFCD, Asscessed May 5, 2018, https://www.hcfcd.org/ hurricane-harvey/flooding-impacts-in-connection-with-the-reservoirs/.

41 Regulated floodways and the 100-year (1% chance) floodplain and regulated floodway are SFHAs, but the 500-year floodplain (0.2% chance) is not. Homes in the 500-year floodplain are not required to have to have flood insurance.

42 Michael Keller, Mira Rojanasakul, David Ingold, Christopher Flavelle and Brittany Harris, “Outdated and Unreliable: FEMA’s Faulty Flood Maps Put Homeowners at Risk,” Bloomberg (New York, NY), Oct. 6, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2017-fema-faulty-flood-maps/.

43 Joel Eisenbaum, “Harris County approves tough elevation rules for new construction in floodplains,” Click2Houston, Published December 5, 2017, Accessed May 5, 2018, https://www.click2houston.com/news/harris-county-approves-tough- new-elevation-rules-for-new-construction.

44 “A Defining Moment for Houston: Mayor Praises Council Adoption of Flood Prevention Reforms as Major First Step Toward Strengthening City,” City of Houston, Accessed May 5, 2018, http://www.houstontx.gov/mayor/press/flood- prevention-reforms-approved.html.

45 Al Shaw, Neena Satija and Lisa Song, “Buyouts won’t be the answer for frequent flood victims in Texas,” The Texas Tribune and ProPublica (Austin, TX and New York, NY), Nov. 2, 2017, https://features.propublica.org/houston-buyouts/ hurricane-harvey-home-buyouts-harris-county/.

46 “Wild River: A pictorial petition,” (Harris County Houston Ship Channel Navigation District, City of Houston, Harris County, Houston Chamber of Commerce, Buffalo Bayou Property Owners Association, Houston, TX, 1937), 1, https://www.hcfcd.org/media/1345/wildriver1937_hcfcd_created.pdf.

47 “Harris County Flood Control District Voluntary Home Buyout Guidance,” (HCFCD, 2016), Retrieved Jan. 2018.

48 “Overview of the Uniform Act (URA),” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Accessed Apr. 25, 2018. https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/affordablehousing/training/web/relocation/overview.

49 James M. Wright, “Chapter 15: Commonly Applied Floodplain Management Measures,” in Floodplain Management: Principles and current practices, 15-14.

50 Dan A. Tarlock et al, “Living with Water in a Climate-Changed World,” 491.