6 Precedents

Mitigation through land acquisitions has the potential to achieve many goals, but the most obvious is that the process “intend[s] to purchase damaged parcels from homeowners who are unwilling or unable to rebuild”61 and thus “providing the financial resources to relocate to a less vulnerable area.” However, obtaining the financial resources and/or assisting in the relocation to a new home are still difficult parts of the process that need more creativity. For example, it may be worthwhile to consider how compensation can be more than just monetary.

If there is one thing for certain, it’s that the overarching goal is to move people to live in areas of less risk, so “relocation is key” to the success of land acquisitions as a mitigation strategy.62 Planning for the relocation of participants “is crucial for maintaining communities, for gaining public support, and for long-term economic development.”63 It is up to planners to see the opportunities in identifying areas where development of less risk can occur and assisting homeowners with their transition, taking into full consideration their needs. The daunting task of relocating whole communities can stifle most pursuits in administering a more robust acquisition program, but it should be emphasized that options need to be available for individuals as well as communities, which should not hinder the engagement of local land use planning and the tools it provides from developing solutions for all.

Although not yet integrated into wider practice, as mentioned before, there are specific cases of communities attempting to mitigate through acquisitions while also achieving other community needs or goals. Due to an upstream flood control project, Allenville, AZ, a predominantly rural black community, was increasingly burdened with flooding. Through a thorough public process with community input, the relocation of the small town in the early 1980s was considered a success since most all citizens participated and expressed satisfaction with the move.64 In 1978, Soldiers Grove, WI waited too long for structural mitigation all while its downtown was in severe decline because of the recurring floods. The city is now known for it “multi-purpose recovery” that not only involved moving the town to higher ground but an opportunity to reinvest in the downtown area, making it the first energy-efficient and solar-heated business district in the nation.65 There are many other stories of small towns across the country that have completely relocated themselves in the face of flooding, but fewer that can boast positive outcomes.

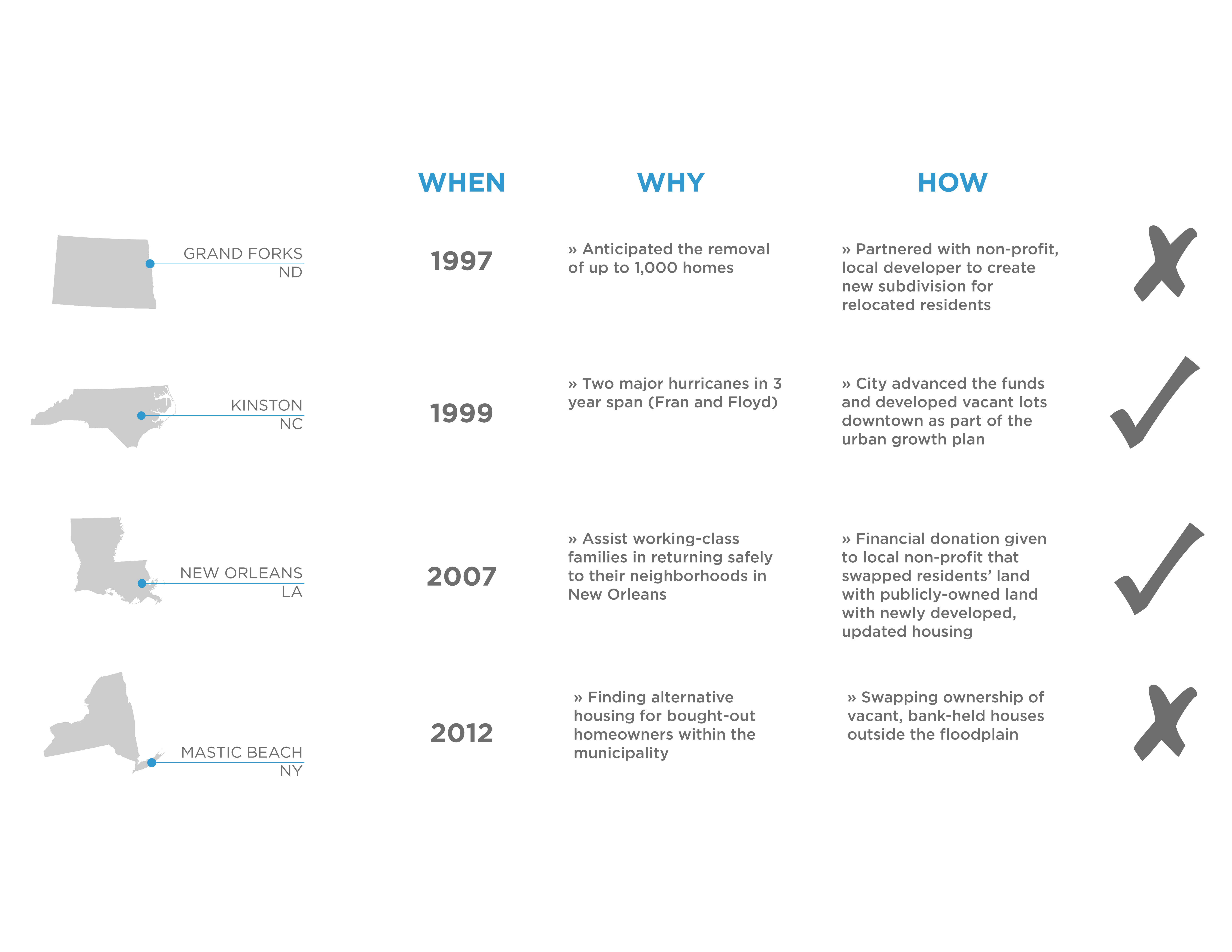

Whole town relocations aside, for the sake of Houston, it was important to look at precedents where acquisitions or buyouts were pursued in conjunction with other city initiatives to better address the issue of creating a destination for participants, particularly when only portions of a city are targeted. Helping residents envision their future in a new location is one of many ways planners can improve the buyout process, promoting safer development practices and insuring residents don’t end up in similar situations elsewhere. Additionally, it was also essential to investigate precedents that incorporated resources outside of federal funding, as extending beyond that resource allowed local communities more flexibility in the structure of their acquisition programming. Although acquisitions should be anticipated prior to disasters through planning, implementing them post-disaster increases the amount of participation and support from the community, as the event is fresh in their minds. I chose four precedent cities (see Figure 9) that implemented an acquisition or buyout program after a major flooding event and coupled it with other planning initiatives, tools, or resources to strengthen the impact of the mitigation strategy for their respective communities. Each city experienced varying degrees of success which better outlines the strengths and weakness of different approaches.66

Figure 9

Grand Forks, ND (1997)

On the border of North Dakota and Minnesota, Grand Forks was one of many towns devastated by the Red River Flood of 1997, which was the worst flood to hit the town on record. As part of the recovery the City of Grand Forks anticipated a large amount of buyouts, and as the administering agency, knew that new housing had to be built in its place. The city partnered with Grand Forks Homes, a local nonprofit housing developer, and using Community Block Development Grants specific for disaster-affected communities, developed new neighborhoods outside of the floodplain. About 802 homes were purchased and 180 homes developed. Few of the newly developed homes has sold by 1999 as the homes were “out of the price range” for many of the anticipated buyers (prices ranged from $105,000 to $147,000 while older homes purchased ranged from $50,000 to $80,000).67 There was also a lack in other community amenities, such as schools, and the site of the neighborhood itself was on the opposite side of the city. Eventually prices for the homes were dropped, facilitating more move-ins but it is unclear if by that time it was mostly bought-out residents.

The city partnering up with a local organization to provide housing for its residents, especially after quickly acknowledging the substantial amount of units that were not to be rebuilt, was an admirable and innovative forward step towards combining development and mitigation through acquisitions. Grand Forks replacement housing project could have been a more successful had it took into consideration the needs of its intended audience.

Kinston, NC (1999)

Located along the Neuse River, Kinston, North Carolina had suffered repeated flooding after two hurricanes hit the region in the late 1990s. Hurricane Fran devastated the community first in 1996 and was followed shortly after by Hurricane Floyd in 1999, while the city was still recovering from Hurricane Fran. Facing storms back to back gave more than enough motivation for the local community to participate in buyouts, totaling in over 90% of residents in the 100-year floodplain moving (approx. 775 acquisitions).68 The City of Kinston was able to respond quickly to residents interested in selling by advancing local funds while awaiting federal funding to arrive and using momentum from the Hurricane Fran funds.

In an effort to retain its tax base, the city structured a buyout and relocation program, which plugged into many other community goals such as revitalizing downtown, creating affordable housing and elderly housing and addressing polluted sites. For example, to tackle both affordable housing and the revitalization of the downtown area, the city initiated a program called “Call Kinston Home,” which had a goal of building affordable, owner-occupied homes on vacant lots in distressed neighborhoods where infrastructure was already in place.69 The city received support from the Governor’s relief fund and the Department of Corrections through inmate labor for making construction materials. The city also repurposed an abandoned high school building into elderly housing units.

The story of Kinston demonstrates that buyouts don’t have to only move people out of harm’s way, but can serve as “the impetus and implementation tool for a host of other smart growth initiatives.”70 Kinston’s recovery is advertised by most, including FEMA, as a success in “innovative floodplain management”71 for its ability to plan and mobilize to vacate the floodplain without undermining the growth of the city. Post-Floyd, Kinston adopted a new growth plan that “fully integrated” mitigation into the planning and redevelopment process, making it a model for other communities.

New Orleans, LA (2007)

There’s no need to explain the impact of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans, LA, but what is lesser known is the work of a nonprofit initiative focused on helping struggling families return to their neighborhoods safely through land swapping. Project Home Again (PHA) was a local nonprofit founded in 2007 by a generous gift from founders Leonard and Louise Riggio specifically to create 100 homes for displaced families in New Orleans.72 The overall all mission of the organization saw housing as “a vehicle to help low-and moderate-income families re-root in New Orleans and provide the stability they needed to reestablish their lives.”73 The PHA approach was to reconcentrate redevelopment in select neighborhoods by building energy efficient and storm-resistant housing that the households wouldn’t normally be able to afford. To achieve this, PHA used the mechanism of land swapping to facilitate moves back into the neighborhoods. Working with the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA), which had vacant land holdings, PHA would use buildable lots of participants, purchase lots from NORA or exchange properties with NORA for ones within their target areas as sites for their housing development.

PHA did reach its goal of developing 100 homes, though the organization is no longer in operation today. PHA was successful in serving its target audience and contributing to the redevelopment of City of New Orleans. It is unclear how much risk is reduced, given that the housing is built to a higher standard but still within the vulnerable areas, which is something to consider when designing a redevelopment process. However, despite being a very specific organization with an unusual source of stimulus funding, PHA’s model of utilizing existing public land holdings as a resource for acquisition of other parcels and strategic redevelopment is an idea that can be furthered in other communities.

Mastic Beach, NY (2012)

Mastic Beach, NY was one of many Long Island communities hit hard by Superstorm Sandy in 2012. In addition, Mastic Beach was also hit hard by the 2008/2009 housing crisis. Post-Sandy, there was a growing interest in buyouts. Although not beneficial for a newly incorporated village, many residents participated in either the NY Rising Buyout Program or NY Rising Acquisition Program. Bought-out residents wanted to stay in the area but there were few replacement housing alternatives. Just outside the floodplain, were vacant homes, relics of the housing crisis, that community members saw as a potential solution.74 Former student Rebekah Armstrong of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, under the supervision of Prof. Daniel D’Oca, investigated the possible mechanisms for facilitating the move inland for Mastic Beach. Armstrong recommended the community land trust model to unlock the pre-foreclosed housing stock and cottage zoning75 to increase density that aligned with character concerns of the community.76 Unfortunately, the vacant properties were never successfully repurposed for bought-out residents, but what is exceptional about the Mastic Beach story is the willingness to look into existing resources, such as vacant properties, and attempt to structure that into a relocation program for that community.

New subdivisions, vacant lots, land swapping and vacant housing all demonstrate, whether successful or not, the importance of augmenting the acquisition process with local resources and mechanisms to achieve stronger outcomes. There are local communities attempting to make stronger connections between mitigating for future risks through acquisitions and the growth of their cities. These precedents demonstrate that with augmentation through tools commonly used in comprehensive planning to achieve community goals, buyouts and other related acquisitions can be part of greater city-building processes. More importantly, the stories of these communities show that there is room for innovating and improving the integration of hazard mitigation into local land use planning.

61 Ann Siders, “Anatomy of a Buyout,” 2.

62 Ann Siders, “Managed Coastal Retreat: A legal handbook on shifting development away from vulnerable areas,” (Columbia Law School Center for Climate Change Law, New York, NY, 2013), V.

63 Ann Siders, “Managed Coastal Retreat,” 114.

64 Ronald W. Perry, and Michael K. Lindell, “Principles for Managing Community Relocation as a Hazard Mitigation Measure,” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 5, no. 1 (1997): 53.

65 William S. Becker, “Rebuilding for the Future: A guide to sustainable redevelopment for disaster-affected communities,” (US Department of Energy, Washington D.C., 1994), 14.

66 Defining success as bought-out participants transitioning to the new sites.

67 https://www.hudexchange.info/onecpd/assets/File/CDBG-DR-Case-Study-Residential-Buyout-in-Grand-Forks-ND.pdf

68 Monica Olivera McCann, “Case Study of Floodplain Acquisition/Relocation Project in Kinston, NC After Hurricane Fran (1996) and Hurricane Floyd (1999)” (thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2006), 22.

69 Monica Olivera McCann, “Case Study of Floodplain Acquisition/Relocation Project in Kinston, NC,” , 40.

70 Monica Olivera McCann, “Case Study of Floodplain Acquisition/Relocation Project in Kinston, NC,” , 50.

71 https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/3807

72 Marla Nelson, “Using Land Swaps to Concentrate Redevelopment and Expand Resettlement Options in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans,” Journal of the American Planning Association 80, no. 4 (2014): 429.

73 Marla Nelson, “Using Land Swaps to Concentrate Redevelopment and Expand Resettlement Options in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans,” Journal of the American Planning Association 80, no. 4 (2014): 429.

74 Robert Freudenberg, Ellis Calvin, Laura Tolkoff, and Dare Brawley, “Buy in for Buyouts: The case for managed retreat,” (Lincoln Land Institute - Policy Report Series, 2016) 50.

75 https://aging.ny.gov/LivableNY/ResourceManual/PlanningZoningAndDevelopment/II2c.pdf; Cottage zoning - “very small houses built densely or in very close proximity to one another.”

76 Rebekah Armstrong, “Mastic Beach Village: Trust Us,” In The Storm, The Strife, and Everyday Life: Sea Changes in the Suburbs, Studio Report, (Fall 2014), Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Instructor: Dan D’Oca. https://issuu.com/ gsdharvard/docs/thestormthestrifeandeverydaylife/9.